The musical genre known as “the blues” emerged around the turn of the 20th century. It is composed using a distorted pentatonic scale and a call-and-response song form.

Over the past century, the blues has served as the foundation for almost all American popular music genres, including jazz, R&B, rock, and hip-hop.

The blues tradition, however, is a little bit different; it is wider, deeper, and more creative. The history of artistic resistance is what has flowed like a river through the area that is now claimed by America, spawning a great deal of its culture.

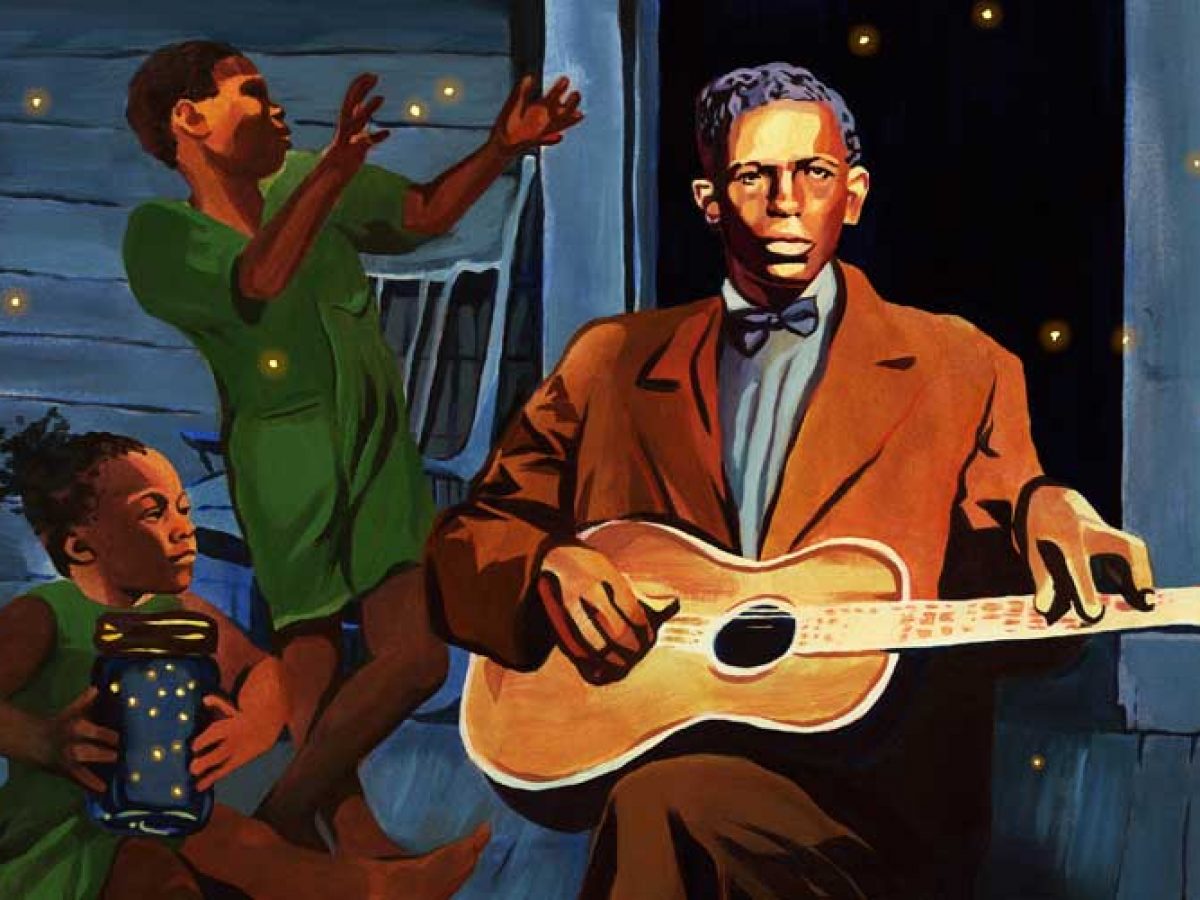

The black community has used codes throughout the history of this nation to navigate life despite the burden of white imposition through language and art. Over the past century, the conditions for perseverance have changed, and the blues tradition has continuously changed to reflect these changes. It can be heard in a lot of contemporary electronic music, some jazz styles, and the forward-thinking rap voices of many rappers. One of the first creators of the Delta blues was Charley Patton. He was also among the first significant figures in American folk music to favor a more intimate style over third-person narration and conventional morality ballads. It was a daring step.

“This is one of the fundamental distinctions between blues and the black music that came before it,” Robert Palmer writes in Deep Blues: A Musical and Cultural History of the Mississippi Delta. “The singer is so involved that in many cases his involvement becomes both the subject and substance of the work. . . . In the context of its time and place it was positively heroic. Only a man who understands his worth and believes in his freedom sings as if nothing else matters.”

The Mandekan phrase yere-wolo, which is used in portions of West Africa, effectively means “to give birth to oneself.” It alludes to the realization of one’s inherent strength and essential qualities, as well as the manifestation that results from this realization. There is no equivalent in English, but this idea has grown to be essential to who we are as Americans, largely because of black music.

There is tenuous but persistent work—a kind of yere-wolo—going on in every blues-driven music. It involves asserting oneself and eliminating constraints, frequently by choosing to ignore them. Patton exemplified everything. He sang of longing and escape with tanned-leather tension and squeezed-up toughness ringing in his voice, but he also exuded unwavering confidence. He behaved according to his terms regardless of where he went, how he suffered, or who he courted.

Patton established a standard for much of the American music that followed, including Little Richard, Betty Davis, and Solange, by doing this.

I’m goin’ away, to the world unknown

I’m goin’ away, to the world unknown

I’m worried now, but I won’t be worried long

—“Down the Dirt Road Blues,” Charley Patton (1929)

Patton, like the majority of the early blues singers, was a combination of confessor, Romeo, and wise man. He spoke from his own viewpoint, but he also provided insight into the goals and aspirations of others.

Fella, down in the country, it almost make you cry

Fella, down in the country, it almost make you cry

Women and children, flaggin’ freight trains for rides

—“’34 Blues,” Charley Patton (1934)

The so-called “city blues” genre played a significant role in the blues’ emergence as a popular musical genre in the 1920s. It featured ladies throwing irreverence and provocation, like Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith, yet dressed appropriately for company. They were changing the values of polite society, not asking for a place in it. They didn’t find it interesting unless they could figure out where they fit into it.

If I go to church on Sunday

Sing the shimmy down on Monday

Ain’t nobody’s bizness if I do

If my friend ain’t got no money

And I say, “Take all mine honey”

’T ain’t nobody’s bizness if I do

—“’Tain’t Nobody’s Biz-ness If I Do,” Bessie Smith (1923)

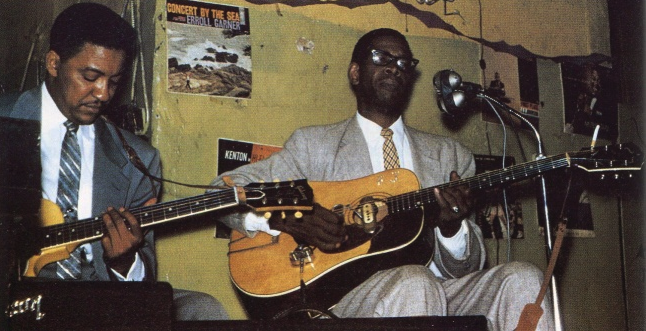

The impact of the Southern blues spread across the country in the decades that followed, evolving into the electric blues in Chicago and fusing with the gospel to produce doo-wop in black neighborhoods across the nation. It influenced rockabilly, R&B, and eventually rock ‘n’ roll (whose name came from a coded term for sex).

Along the way, there was jazz, which acknowledged significant blues influence but developed independently from these other traditions more than is frequently acknowledged. In New Orleans, among the professional bands that had developed from the long-standing brass band tradition of the city, jazz first appeared. In Blues People: Negro Music in White America, Amiri Baraka writes “they played most of the music of the time: quadrilles, schottisches, polkas, ragtime tunes.”

Jazz’s foundation was unquestionably the blues. It was evident in the syncopated tapestries, African-inspired harmonies, and bending notes that frequently appeared to mimic the whinnies and groans of the human voice. However, jazz’s origins were both international and largely commercial: they were inspired by both the unapologetically regional patois of the blues and the vocational of society bands.

Big band jazz hewed more closely to the demands of a paying concert audience, as Baraka notes, as it gained in popularity. The blues inherent in the music—the self-styling, the low fervor, the avowed displays of pride and desire—was given a smaller margin of error.

Many jazz artists transitioned from dancing music to tight bebop combinations in the 1950s. The fundamental truths of the blues persisted inside it, though they were frequently expressed only through musical means. Jazz songs with lyrics tended to be adaptations of show tunes. Blues poetry typically proved to be too much for the jazz economy, largely due to the demands of white audiences and promoters, with a few notable exceptions. Jazz singing almost completely lost the lowbrow humor and social realism that had characterized the works of musicians like Rainey, Cab Calloway, and Fats Waller.

In the end, during the Second Great Migration, it was soul and funk that more fully assumed the blues mantle. James Brown is without a doubt the greatest blues performer of the latter part of the 20th century. He combined the unyielding subjectivity of blues storytelling with the hard-charging, virtuoso ambitions of the jazz musician.

Even his overtly political music was often lodged in the first person:

I’ve worked in jobs with my feet and my hands

But all the work I did was for the other man…

—“Say It Loud—I’m Black and I’m Proud,” James Brown (1968)

By the late 1980s, hip-hop had taken over from artists like Brown, Betty Wright, Eddie Kendricks, and Gil Scott-Heron. Rappers today spit poetry that is more energetic and well-written than anything previously heard in popular music. The continuum is evident, though.

In his verse on Isaiah Rashad’s “Shot You Down,” ScHoolboy Q raps:

Not a dollar on me, this home invasion a payday

Two-time felon, they jerkin’ me on my pay rate

Slavin’ all these hours but couldn’t shake that my rent late

Makin’ eight a hour, I’m leanin’ toward my AK

Moms think I’m vicious, don’t want me ’round the kitchen

My living room, bathroom, my bedroom was evicted

Missin’ from your homeroom, my good grades was crippin’

Before I even learned division, nigga, I learned the mission

See I’m from where fiends scratch that itch, won’t hit the lotto

And I’m from where fiends fix that fix and not a bottle

This poetry reflects both adversity and inventiveness. The focus is on ScHoolboy—on his intelligence and determination—rather than on a political system that criminalizes poverty and provides so few options to so many people.

Hip-hop thrives in areas that are as economically depressed and socially isolated as the former Mississippi Delta plantations. Paramilitary police forces and parole boards in American cities have adopted the oppressive tactics of Southern sheriffs and vigilantes. If the African American ethic of grace-filled survival and a sense of empowerment despite denial is the foundation of the blues, then its tragedy and triumph are that it continues to exist.