In a recent Boston Globe article, Ty Burr declared, “Someday we may look back on 2016 as the year the movies died. That’s a blanket statement, but nothing that came out of the multiplex this summer contradicts it.”

Burr acknowledges that there was a lot to see in the arthouses, but if you only judge the state of the industry on the quality of summer tentpole blockbusters, then yes, movies may seem to be in a very sorry state. But open the lens up a little wider, and there is an entire galaxy of stuff going on—challenging/complex films (where the flaws are more interesting than anything you’d see in a more risk-averse film), first features, foreign films, microbudget films with unknown actors, films doing what films—at their best—have always done.

Outside of mainstream Hollywood, 2016 has been a tremendous year, with films like “The Witch,” “Cemetery of Splendour,” “Krisha,” “The Fits,” “Everybody Wants Some!!”, “The Hunt for the Wilderpeople,” “The Nice Guys,” “Disorder” (the list goes on) … You don’t even have to go far off the beaten track to find an entire landscape of interesting stories told in unique ways.

One of those unique movies is “Kicks,” directed by Justin Tipping, about a teenage guy who tries to recover some stolen sneakers. Even while “Kicks” has problems, even those flaws demonstrate Tipping’s desire to take chances, go for the big gesture, and do so honestly. “Kicks” is a coming-of-age story with many fond nods to earlier movies, but it takes place in its own setting, upending the stereotype of the suburban family. “Kicks” is wise and naive, serious and goofy.

Tipping grew up in Oakland’s East Bay neighborhood and has firsthand knowledge of the teen sneaker cult, which emphasizes the importance of sneakers as potent status symbols. (Those who condemn “bling” and “conspicuous consumerism” likely have never experienced poverty.) “I am somebody,” is the message sneakers convey. Additionally, wearing sneakers exposes you to people who want what you own. In “Kicks,” there are moments when time seems to be moving at an incredibly slow pace, and there are other scenes where the neighborhood’s jumbled reality is clearly felt. From the very first frame, Tipping and director of photography Michael Ragen establish a subjective, poetic ambiance that is immensely helpful to the movie’s pure emotionalism.

The perspective is always clear: This is the world as seen by 15-year-old Brandon (Jahking Guillory), who is shorter and smaller than most of his classmates. Brandon wishes he were bigger and taller, but he most desires to have a great pair of sneakers, specifically the magnificent black and red Air Jordans he sees on another boy’s feet in the school hallway.

Christopher Meyer and Christopher Jordan Wallace, the son of Notorious B.I.G., who plays want tobe ladies’ guy Albert, are Brandon’s two closest buddies with whom he spends time. There aren’t any parents in sight. The three young performers have a natural affinity with one another that is motivated by genuine affection. Although each character has quirks that drive the others crazy (Albert brazenly buys extra-large condoms while Rico and Brandon roll their eyes at each other; Albert has never had a girlfriend in his life), they all have each other’s backs.

When things get tense, their interaction as a group offers the comedy that the movie needs. Brandon ultimately purchases a nice pair of Jordans from a man selling them out of the back of his truck after saving up his money. Like Tony Manero in “Saturday Night Fever,” Brandon struts out of the house wearing them, only to be attacked shortly after by a gang led by the infamous silver-toothed Flaco (Kofi Siriboe), who promptly steals Brandon’s sneakers off of his feet. In order to help him in his mission to recover his sneakers, Brandon persuades his recalcitrant oaf friends to assist him.

With the help of Brandon’s two stoner cousins who are eager to assist their much-younger relative, the lads meet up with Brandon’s menacing and yet wise ex-con Uncle Marlon (Mahershala Ali, in a magnificent Mariana-Trench-deep performance) while on their journey to retrieve the sneakers. Everyone cautions Brandon and advises him to throw away the sneakers because Flaco is such bad news, but Brandon claims,”They’re not just shoes. They’re fucking J’s.” Nobody really can argue with that.

Once in Oakland, the boys are thrown into a perplexing, humorous, and frightening maelstrom. Tipping and Joshua Beirne-Golden co-wrote the script, and one of its finest aspects is how Flaco develops complexity all his own. This is because Tipping doesn’t just follow Brandon, but also the sneakers, so we can see where Flaco puts them and who Flaco gives them to. Due to this decision, “Kicks” has an ambivalent undertone that provokes contemplation.

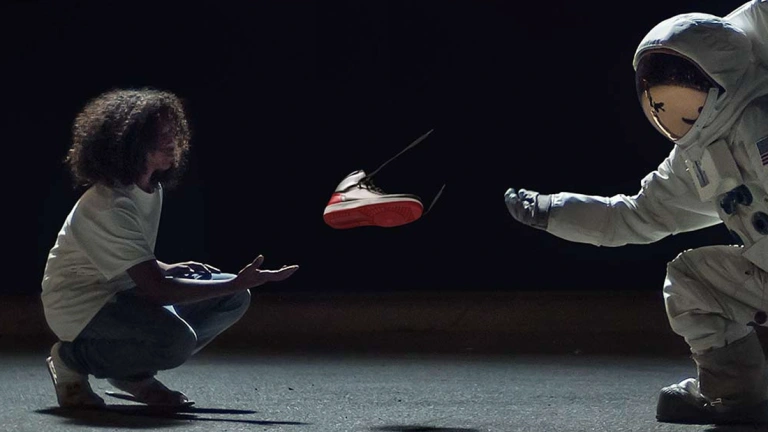

The movie starts out with Brandon confessing in voiceover that he has always wanted to travel to space since it is peaceful and no one can bother you there. In his nightmares, he sees a “spaceman” companion—a guardian angel astronaut—who appears by Brandon’s side, hovers above the streets, gives him quiet encouragement, or is simply keeping watch over him. The things Brandon wants most for himself—freedom, peace, and solitude—are almost as important to him as stylish shoes. Tipping carefully selects the astronaut appearances, so when the spaceman does show up, it’s not a stunt or a device. That is the entire point.

The astronaut, wearing a mirrored helmet, hovers over the mayhem and beckons Brandon in one direction or another. The fact that the astronaut occasionally encourages questionable decisions is proof that Brandon is still only 15 years old. In addition to wanting to belong, he also wants to be himself. How do you bring those two things together? The teenage conundrum.

Brandon steals a gun at one point to have in case he needs it later on in the adventure. The Chekhov’s gun plot point is a defect, although a minor one. From chase scenes to party scenes to group conversations, “Kicks” ricochets along on its own energy in so many different ways. The tension it creates is hollow because the gun is from a less creative, less intimate film.

However, the strange thing about a fault in a movie like “Kicks” is that it brings attention to how excellent and powerful the remainder of the film actually is. Elia Kazan frequently discussed the “spine” of his movies and stressed the importance of this spine being visible in each scene, each character, and each passing second. He was able to make his artistic decisions after grasping the significance of the spine. To pull things off, you need a really clear vision, and Tipping has that vision. It’s a stunning movie and a significant debut for the director.